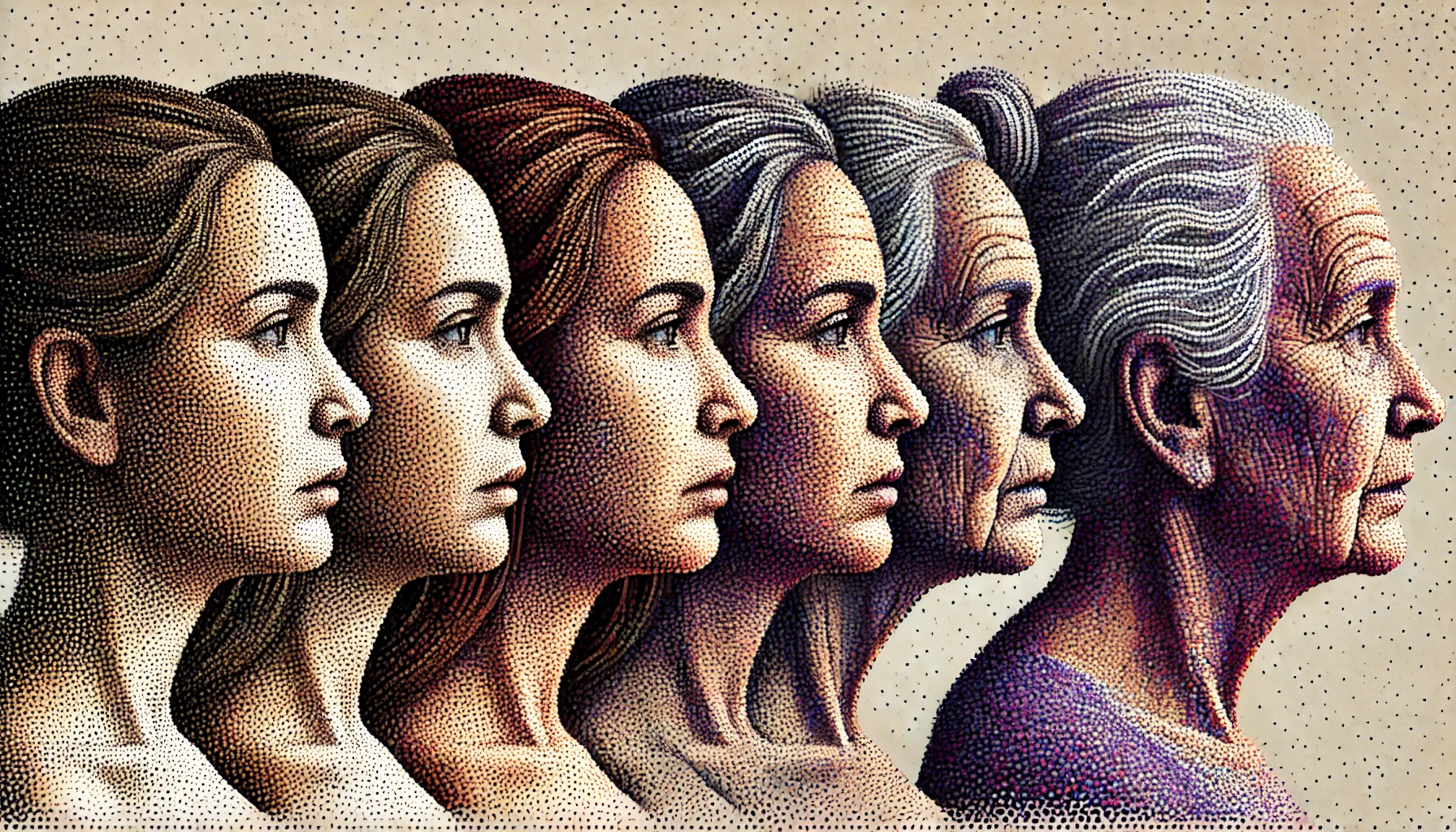

Aging is life’s great certainty. From birth, the countdown begins—a slow, relentless decline leading to our final chapter. Yet, despite its inevitability, aging remains one of biology’s deepest mysteries. Is it written into our DNA, or just a lifetime of accumulating damage?

For decades, scientists have chased this question, trying to uncover forces driving aging. Some argue for genetic programming—an internal clock ticking toward an expiration date. Others see it as sheer wear and tear, with our bodies breaking down under relentless stress. The truth likely straddles both theories.

The Blueprint: DNA Damage and Genetic Instability

Trillions of chemical reactions pulse through your body every second. Cells divide, proteins fold, and oxygen fuels metabolism. But none of this is perfect—mistakes happen, and over time, they add up. At the core of aging is DNA damage. Every day, your genetic material is attacked by UV rays, pollutants, toxins, and free radicals—unstable molecules that sabotage cellular integrity.

Cells have repair mechanisms like the nucleotide excision repair system to fix broken DNA. But these aren’t flawless. Over decades, errors accumulate, slowing cell function. The result? Mutations that fuel diseases like cancer, where cells grow out of control. Think of DNA as an instruction manual. With age, pages wrinkle, ink fades, and words blur. The body struggles to read its own guide, and maintenance begins to fail.

The Telomere Problem: The Countdown to Cellular Senescence

Cells don’t last forever. Each time a cell divides, it copies its genetic material. But there’s a catch: the chromosome ends—called telomeres—shorten with every division. Telomeres are like the plastic tips on shoelaces, keeping DNA from fraying. Eventually, telomere shortening, often worsened by oxidative stress, triggers cellular senescence—a limbo state where cells stop dividing but remain metabolically active. These cells continue consuming energy and releasing inflammatory molecules, accelerating aging and tissue damage. This phenomenon aligns with the Hayflick Limit, which describes the finite number of times a normal human cell can divide—typically around 40 to 60 divisions—before it reaches senescence. This limit acts as a safeguard against uncontrolled growth but also contributes to aging as the body’s capacity for cell renewal declines over time.

Semescence process acts as a double-edged sword. On one hand, it prevents damaged or precancerous cells from replicating. On the other, the accumulation of senescent cells over time leads to chronic inflammation and tissue dysfunction, contributing to age-related diseases.

Cells produce telomerase, an enzyme that rebuilds telomeres, however they don’t produce it enough, and in some point cells reach their Hayflick limit. However, large enough quantities still exist in certain adult cells, such as sperm, cancer and stem cells, which maintain their regenerative abilities and is the reason why cancer cells can achieve uncontrolled growth.

The most adult cells have minimal telomerase activity, ensuring that aging progresses. While telomerase activation could, in theory, slow aging, excessive activation carries a risk—uncontrolled cell growth and cancer. Researchers are now exploring ways to safely enhance telomerase without triggering malignancies. Without functional telomeres, the body becomes vulnerable. The immune system weakens, infections become deadly, skin loses elasticity, and healing slows to a crawl.

Epigenetic Drift: When Cells Forget Their Identity

DNA is the blueprint of life, but epigenetics is the control system, flipping genetic switches on and off. Epigenetics is the study of how gene activity is regulated without changing the DNA sequence itself. Aging scrambles the epigenetic code. Epigenetic changes have been found to be influenced by lifestyle factors such as diet, exercise, and environmental exposures, leading to differences between a person’s biological and chronological age. These modifications can either accelerate or slow down aging depending on external conditions. Genes that should be active shut down, while dormant ones wake up.

Epigenetic changes occur due to chemical modifications to DNA and its associated proteins, such as DNA methylation and histone modification. They regulate gene activity without changing the underlying DNA.

- DNA Methylation:

- This involves the addition of a methyl group (CH₃) to cytosine bases in DNA, typically at CpG sites (regions where cytosine is followed by guanine).

- Methylation generally silences genes by blocking transcription factors or recruiting proteins that compact DNA, making it less accessible.

- Over time, epigenetic drift can cause improper methylation patterns, leading to gene misregulation and aging-related diseases.

- Histone Modification:

- DNA is wrapped around proteins called histones, forming a structure called chromatin.

- Chemical changes, such as acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, or ubiquitination, can alter histones, influencing how tightly or loosely DNA is packed.

- Acetylation (adding an acetyl group) loosens chromatin, making genes more accessible for transcription.

- Methylation (adding a methyl group) can either activate or repress gene expression depending on the location.

These mechanisms act like molecular on/off switches that determine which genes are active in a given cell at a given time. Over the course of aging, errors in these regulatory processes accumulate, leading to a decline in cellular function and increased susceptibility to disease. Researchers are exploring ways to reprogram epigenetic markers to potentially reverse aging at the cellular level.

Aging: Programmed or Just Damage?

Is aging a pre-written fate or a lifetime of accumulated damage? The programmed aging theory suggests that evolution has set limits on lifespan through genetic and hormonal signals, ensuring population turnover. The damage accumulation theory argues aging is just entropy—oxidative stress, DNA errors, and cellular waste piling up until systems fail. The answer is likely both. Aging follows some genetic rules—like telomere shortening—but random damage accelerates the decline.

The shortening of telomeres and epigenetic changes clearly play a role in aging, but there are several other contributing factors. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, chronic inflammation, and the gradual accumulation of cellular waste all interact in complex ways, further accelerating the aging process. Understanding these mechanisms holistically is key to developing effective interventions that could potentially slow or even reverse aspects of aging. Science is getting closer to slowing, even reversing aging. The most promising methods include:

1. Caloric Restriction & Fasting

Cutting calories triggers sirtuins, longevity genes that boost DNA repair. Fasting also sparks autophagy, a process where cells clean up their own debris, keeping them younger longer.

2. Senolytics: Killing Zombie Cells

Senolytic drugs selectively destroy senescent cells, reducing inflammation and age-related damage. Early trials show potential for longer, healthier lives.

3. Gene Therapy & Epigenetic Reprogramming

Scientists are testing ways to reset gene expression to youthful states. Mice have already shown signs of age reversal—could humans be next?

4. Telomere Extension

Boosting telomerase could lengthen telomeres and slow aging, but there’s a risk—too much telomerase might trigger cancer. Researchers are refining how to harness it safely.

Conclusion: The Future of Aging Science

Aging is no longer just a philosophical question—it’s a scientific problem we are learning to solve. Whether through gene therapy, cellular rejuvenation, or lifestyle hacks, extending human lifespan is within reach. We don’t yet have the key to immortality, but we’re closer than ever to cracking the aging code. And if the clock can be rewound, the first 200-year-old human may already be among us.

More Information

If you’re interested in exploring the science of aging further, here are two highly recommended books:

- “Lifespan: Why We Age—and Why We Don’t Have To” by David A. Sinclair. Amazon

- This book delves into the idea that aging is a disease that can be slowed or even reversed. Sinclair, a Harvard geneticist, discusses the molecular mechanisms behind longevity, including sirtuins, NAD+, and other key longevity pathways.

- “The Telomere Effect: A Revolutionary Approach to Living Younger, Healthier, Longer” by Elizabeth Blackburn and Elissa Epel. Amazon

- Written by a Nobel Prize-winning scientist, this book explains how telomeres influence aging and how lifestyle changes can help preserve telomere length for better health and longevity.